|

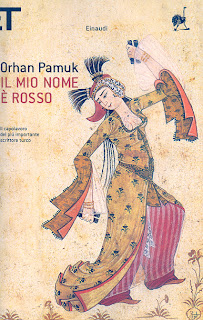

| F.T.Marinetti, Fillìa, La cucina futurista, Sonzogno, Milano 1932 (immagine tratta dal link) |

|

|

(immagine tratta dal link)

|

Chi mi segue da un po' avrà certamente notato che finora non ho mai scritto nulla sul futurismo, nonostante la grande mania per questo straordinario movimento che ha invaso il mercato negli ultimi anni, rivalutandolo e rivedendolo storicamente.

Sul collezionismo di cimeli e libri futuristi negli ultimi anni si sono versati fiumi di inchiostro. Edizioni di ricordi di collezionisti, mostre dedicate ai libri futuristi e testi critici di vario genere. Tutto ciò è stato il risultato di una passione che ha raggiunto anche la "massa", le persone meno esperte, partendo - come spesso accade - dagli Stati Uniti, un paese che spesso ci batte in lungimiranza.

Solo per citare alcuni esempi, le rarità più richieste sono, ad esempio, il libro imbullonato di Fortunato Depero, costituito da una copertina in cartoncino e fogli di carta legati mediante due grossi bulloni con dadi e copiglie, o i libri di Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, come La cucina futurista, realizzata in collaborazione con Fillìa, o il raro e ricercatissimo Parole in

libertà futuriste olfattive tattili-termiche.

|

| F.T.Marinetti, Parole in

libertà futuriste olfattive tattili-termiche, Edizioni

futuriste di “Poesia”, Roma, Lito-latta, Savona 1932 (immagine tratta dal link) |

Il futurismo, per i suoi risaputi legami con il fascismo, è un movimento che nel secondo Dopoguerra è stato molto scomodo e per questo motivo largamente ignorato. Intorno al principio degli anni Sessanta è stata avviata una operazione di recupero dei suoi apporti positivi, che furono adattati alle necessità dell'arte e della letteratura della neoavanguardia. La sua fortuna, da quella data, non è mai cessata.

In proposito amo citare un testo di cui ho discusso in un

post,

La collezione di Giampiero Mughini, che per quanto riguarda il collezionismo librario del Novecento risulta imprescindibile.

Ad un certo punto, parlando della questione del rigetto del futurismo negli anni Cinquanta, Mughini affronta

l'esempio di Benedetta Marinetti, vedova di Filippo Tommaso. La

Marinetti all'inizio degli anni Cinquanta si trovava letteralmente

alla fame e conservava nella sua casa di campagna, dalle parti di

Tivoli, un grosso numero di capolavori del futurismo, da quadri a

libri, sculture, manifesti e molto altro. Ma, come sottolinea

Mughini, negli anni dell'immediato Dopoguerra l'interesse nei

confronti di quei cimeli era pressoché nullo. All'alba degli anni

Cinquanta, finalmente, il Museo internazionale d'arte moderna di New

York le chiede di vendere la sua collezione e lei, a sua volta,

chiede il permesso allo Stato italiano, che le darà il consenso, non

ritenendo il futurismo un movimento importante (in

G.Mughini, La collezione. Un bibliofolle racconta i più

bei libri italiani del Novecento,

Einaudi, Torino 2009, pp.3-53). Al di là della questione dello scacco subìto dagli Stati Uniti, caso peraltro non isolato e pagato ancora oggi dall'Italia a caro prezzo, è interessante notare come un movimento riesca a guadagnarsi un posto in prima fila per una serie di contingenze e rivalutazioni.

|

| Sempresù [Carolus Cergoly], Maaagaala, ristampa anastatica dell'originale del 1928, Arbor Librorum, Trieste 2009 (immagine tratta dal link) |

Dopotutto, è un pò la speranza che anima i librai antiquari che si occupano di cataloghi degli anni Sessanta, a detta loro ancora sottovalutati.

Per concludere, la moda del futurismo ha curiosamente investito anche i cosiddetti "minori": personaggi che hanno preso parte al movimento con interventi sporadici o addirittura isolati, come il triestino Carolus Cergoly, che nel 1928 ha realizzato il libro futurista Maagaala utilizzando lo pseudonimo Sempresù. Oggi questo testo è ricercatissimo e raggiunge quotazioni da capogiro. Di recente è stato anche ristampato in anastatica dalla casa editrice triestina Arbor Librorum, ottenendo un grande successo.

Who is following me since the beginning, maybe have noticed that I've never wrote about Futurism, despite the great mania of this extraordinary movement that has invaded the market in the last years, reconsidering it and revising it historically.

About the collectionism of these books in the last years they have wrote and made a lot. Memoirs, exhibitions and critical texts of all types. All this is the result of the passion that has reached the "mass", the less expert ones, and which has started - as happens oftenly - from the USA, a country that usually looks forward better then us.

Just to make some examples, the most sought rarities are the Fortunato Depero's libro imbullonato, made by a cover and pages binded up with a big bolt and with nuts and cotter-pins. Or the books from Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, like the La cucina futurista, realized in collaboration with Fillìa, or the rare and sought Parole in libertà futuriste olfattive tattili-termiche.

The Futurism, for his well-known relationships with the Fascism, is a movement that caused many problems in the postwar age and therefore it was largely ignored. Then, around the beginning of the 60s, its positive aspects have been rehabilitated and adapted to the literature and avant-garde art's necessities. From that date on, its fortune never ended.

In regards to this, I use to mention an already discussed book (look the post): the Giampiero Mughini's La collezione, which for what concerns 90s book collecting is unavoidable.

At a certain point Mughini, talking about the question of the Futurism refusal in the 50s, makes the example of Benedetta Marinetti, the Filippo Marinetti's widow.

The woman, in the beginning of the 50s, was totally poor and was conserving in her country house, around Tivoli, an enormous amount of Futurism masterpieces: from pictures to books, sculptures, manifests and many other. But, as Mughini clarifies, in the postwar age no one was interested in those things.

Finally at the end of the 50s, the MOMA of New York asked her to sell her collection. Obviously, she asked the permission of the Italian government, which didn't say anything because it considered the Futurism a movement without a particular importance (in G.Mughini, La collezione. Un bibliofolle racconta i più bei libri italiani del Novecento, Einaudi, Torino 2009, pp.3-53).

Now, ignoring the question of the USA role, suffered by Italy very much, it's interesting to notice that some movements can become important thanks to some junctures and revaluations.

After all, is somehow what antiquarian librarians managing catalogues from 60s - which, are according to them, understimated - are hoping that will happen.

To conclude, the Futurism trend has curiously invested also the minor protagonists: people who took part of it with few partecipations, like Carolus Cergoly from Trieste, who has realized in 1928 the futuristic book Maaagaala, using the pseudonym Sempresù. Now the text is very sought and estimated. Recently it has been also reprinted in a facsimile edition from the printing house Arbor Librorum based in Trieste, achieving a great success.

.jpg)